October 2022 – Vol. 2

Mark Your Calendar

True Colors Exhibit @ The Chrysalis - September 26 - October 14

- Exhibit Dates/Times: September 26 – October 14, 2022

- Featuring original art work by Monarch students, families, and staff members

- Original art work and prints are available by suggested donation

- Exhibit is open Tuesday- Thursday from 3:00-5:00pm or by appointment

- Email Erika at emalone@monarchschools.org for an appointment

World Homeless Day Event: Amplified: Sounds of the Community - October 9

We are excited to be joining Voices of our City choir for their 2nd Annual World Homeless Day gathering. AMPLIFIED: SOUNDS OF THE COMMUNITY is a unique and profound artistic collaboration with Monarch School, San Diego Gay Men’s Chorus and La Jolla Playhouse and is a free event to experience our unsheltered neighbors as fellow creatives, artists, and dreamers. The event will feature art work from Monarch students & a special performance by On the Come Up (Monarch’s Dance Team). Seating is limited, you can RSVP online, visit https://www.voicesofourcity.org/worldhomelessday2022

Save the Date for our Fall Student Performance & Art Exhibit

December 9 @ 5pm

December 10 @ 2pm & 5pm

Located at The Chrysalis, Monarch School’s Center for the Arts

Message from the CEO

Sticks, Stones and Stereotypes: Words Hurt When They Carry Stigma

The first time I felt the shame of stigma, I was an anxiety-ridden 3rd grader.

I was confused and on the brink of tears in math class. My teacher was too distracted to recognize that I was struggling to keep up, and though I knew I should ask for help, I was timid. The last time I had raised my hand to seek special attention he made it clear that I should study more and get help elsewhere. Fearing further embarrassment, I kept quiet and sat still, hoping he wouldn’t notice that I wasn’t making any progress. No such luck. He stopped at my desk after complementing the genius of the boy sitting next to me and after a few moments he said simply, “I should have known.” The emotional dam I had cultivated to keep the tears from flowing finally broke, and I wept. My tears did nothing but further irritate him, and adding the final blow he said, “Your parents can’t help you and they’re too poor to pay the tutor, so I guess you’re my problem, is that it?”

Looking back with adult eyes it’s clear that this interaction was damaging in many ways, yet recalling the emotions of the moment resurfaces the sting of what had the most enduring impact. It was the condescension of being labelled “poor”.

If the injury was being made to feel intellectually inept, the insult was the sweeping dismissal of the powerful nuances of my family ties, the bonds that made us feel anything but “poor”. In fact, up until that moment, I had never once considered that term applicable to my circumstances. While we struggled with financial instability, my parents were dedicated, loving, creative and fiercely protective. My family was my source of safety, inspiration and pride. Being labelled “poor” stripped us of our uniqueness and reduced my strengths and weaknesses to a composite that didn’t reflect who I was or who I could become. Never had I considered poverty a defining characteristic, but that changed that day and for years I struggled with the emotional aftermath of realizing that others may view me as “less than”. Those feelings presented as anger, but they masked the pain of insecurity that I battled into adulthood.

In my role at Monarch School, I am often reminded that the words we use to describe our students become their identity, and this intuitive awareness is supported by research. In a thesis study issued by Western Kentucky University, negative labeling of students within their educational environment was correlated to a 20% decrease in academic achievement and lowered self-esteem among the sample population.

When we use social conditions to describe human beings, we rob them of their individuality and deny the validity of their distinct experiences. When we replace one’s singular gifts with a set of stereotypes, we limit potential and resilience. It’s clear that this approach to categorizing people by their circumstances is immeasurably damaging for children. That is why when we refer to an individual as “homeless” we infer that their housing situation defines their character, attributes, and value to society. When we are labelled by a condition, we are no longer free to develop our unique selves but are instead forced to fight against the stigma that the condition brings with it.

This is the primary reason that we at Monarch School reject the term “homeless” to describe our students and their families. Above all else, students who are managing the sustained trauma of housing instability need and deserve the opportunity to understand their own talents and pursue them as a pathway toward healing and stability. If we hope to inspire our youth to dream big and exceed their own expectations, we must start by making space for them to envision their futures, free from the roles we inadvertently assign them with the application of labels.

So, what’s the difference between referring to a person as “unhoused” rather than “homeless”? Ask yourself this simple question, what image does the word “homeless” conjure in your mind when you hear it? If you can immediately call forward a picture of what “homeless” means to you, you’ve answered the question for yourself. This is because the term has, over time, been coopted by popular culture, social systems, and marketing imagery to facilitate a placeholder in our psyche that has become the common concept of what it looks like to survive without a home. We may know intellectually that this is a false narrative, but it exists nonetheless, and it brings with it a crippling set of arbitrary boundaries that poison the well of possibility that all children are born to explore within themselves.

The term “unhoused” connotes a very different reality. It separates the person from the problems they face and reframes the condition as a temporary situation rather than a life sentence. In this way, we accept the present challenges for what they are and leave room for the human at the center of the experience to leverage their talents, set goals and achieve a self-fulfilled life.

If our goal as social care providers and educators is to cultivate each child’s individual skills, let’s start by removing the barriers that come with stigma and use terms that protect the dignity and emotional safety of the kids in our care. Afterall, there are insecure kids in classrooms across the nation attempting to hide in plain sight just like I did. Let’s do right by them. Let’s tell them the positive things they need to hear about their capacity and let labels be a thing of the past.

Reference

Schartung, Jessie, "Examining the Influence of Negative Labeling on Educational Aspirations" (2015). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1521. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1521

Donor Spotlight:

Conrad Prebys Foundation Gift to Camp

![]()

Monarch School was able to take 20 student-athletes and coaches to Whispering Winds Camp in Julian, CA thanks to a generous donation from The Conrad Prebys Foundation. Student-athletes were able to participate in traditional camp activities like archery, swimming, and nightly bonfires. In addition, student-athletes and coaches held team-building activities that focused on personal and team goals, as well as addressing mental health issues.

State of California Grant

Monarch School Project is excited to announce that we are a recipient of the Social Isolation Support grant awarded by The California Department of Education in the amount of $244,550! These funds will go directly to support our mental and behavioral health program. Through this program, we provide students with daily support in the classroom, one-on-one skill- building, individual and family therapy services, as well as art-therapy and sports-based group therapy. Our Emotional Support Team of behavioral specialists, clinicians, counselors, and partner agencies create a safe and stable environment for our students to heal and learn. This year, we are expanding our Mental and Behavior Health programs to benefit other school communities, doubling our impact in the San Diego community.

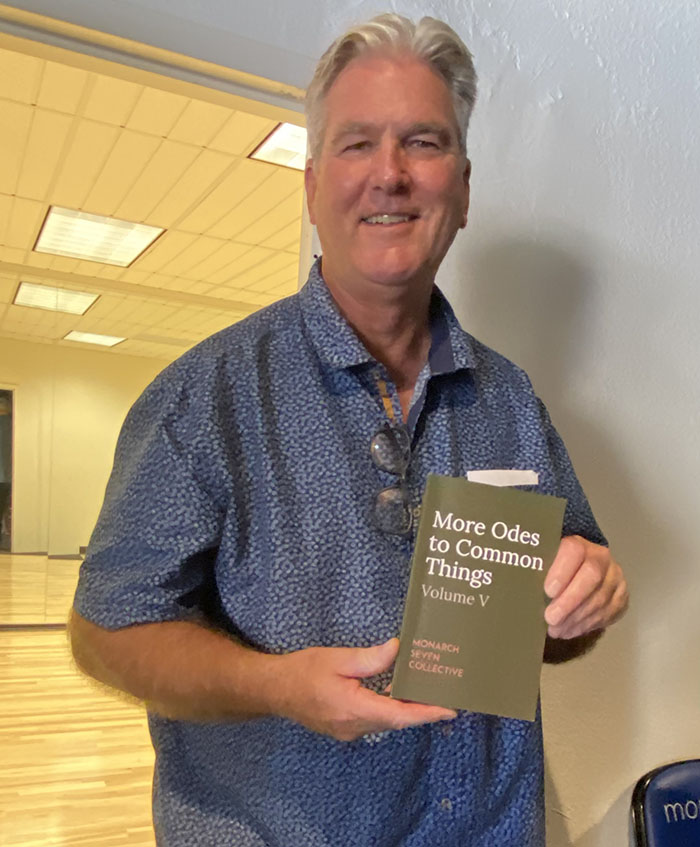

Volunteer Spotlight: Rick Shaughnessy

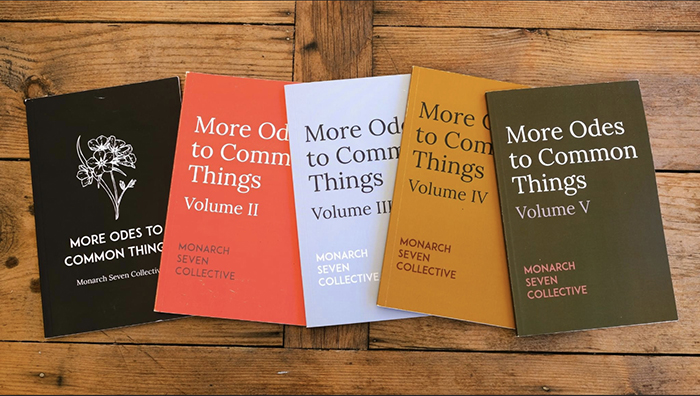

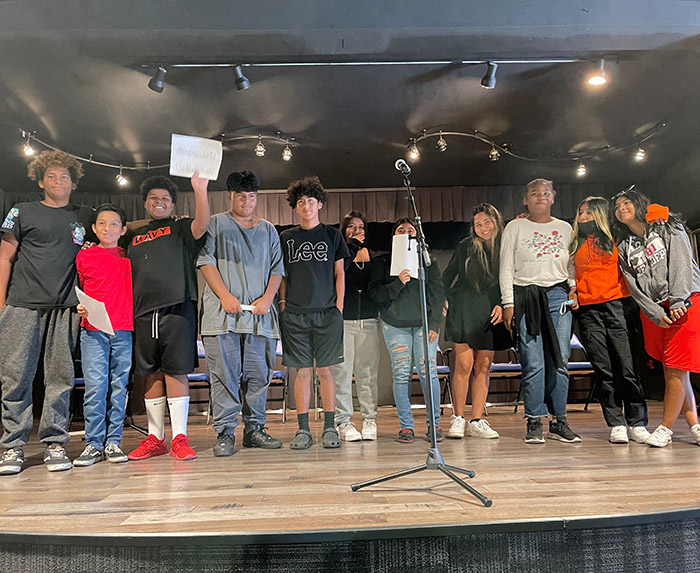

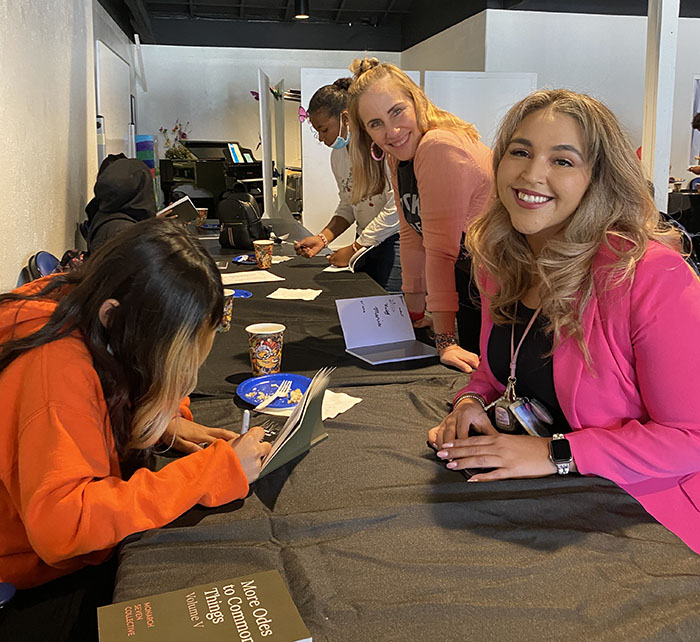

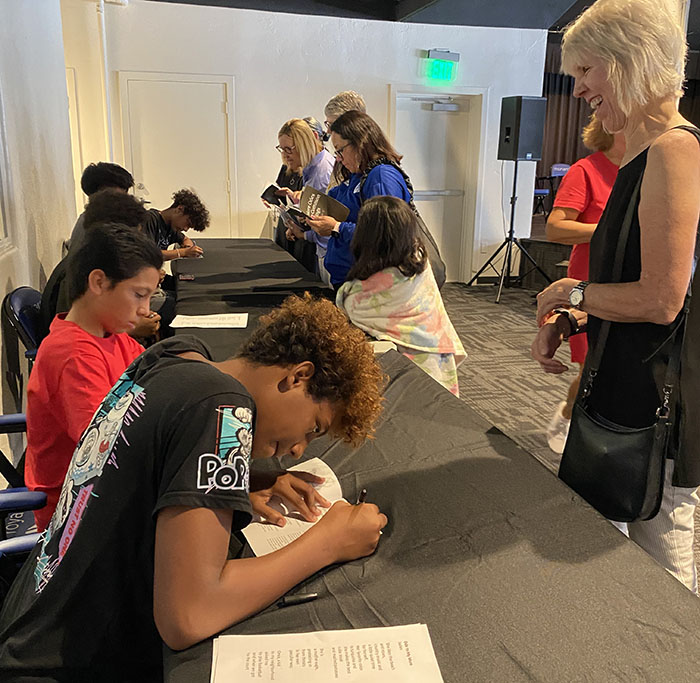

Rick Shaughnessy has been volunteering in Sally Lopez’s 7th grade classroom since 2017. “Mr. Rick,” as students call him, teaches students how to write poetry in the form of odes to creatively express elements of their lives. Each year, students work with Mr. Rick on the writing process, publish a book of poetry, “More Odes to Common Things,” and present their poems to an audience at the annual poetry reading.

Mr. Rick shared that when he had initially asked seventh grade teacher Sally Lopez if he could try having a few students write poems, she seemed a bit skeptical. “I think she sensed that my naïve enthusiasm would prevent the exercise from becoming a complete shamble. So, we started, and I kept her apprised, telling her how good the poems were before I ever showed them to her. Nineteen students wrote odes, and I was so proud of them that I told Sally I wanted to self-publish them in a professionally printed book. She gave me that smiling skeptical look again and her blessing,” says Mr. Rick.

For the first book of Odes, in 2018, one hundred copies were printed. There was Ode to Paper, Ode to Planes, Ode to the Bus, and even an Ode to Pig Latin, which was written in Pig Latin. The first book launch party was at the Coronado Public Library. Students read their poems and signed books. The book was so popular that it had to go back to press two more times that year.

Over the years, Mr. Rick has refined his strategies and approaches for working with students to help them develop their work. In the fall, Mr. Rick devotes a single class session to haiku. Students learn about this form of poetry, read traditional and modern haiku, and try their hands at writing. Many students are naturals to the minimalist form. He also works one-on-one with the students early in the school year writing short personal narratives based on photographs in which they appear. This assignment focuses on using standard English style and grammar to tell a complete, personal story. Later in April, which is National Poetry Month, he leads the 7th grade class in reading and discussing a different poem each day. This is a broad introduction of poets and poetry including works by William Shakespeare, Emily Dickinson, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Maya Angelou, Tupac Shakur, Joy Harjo, Seamus Heaney and others.

Mr. Rick shares, “When we begin the odes project in the spring, we review elements of Pablo Neruda’s style and form and read several of his odes as well as odes written by former Monarch seventh graders. We also talk about a concept of poetry expressed by former U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins. He said: ‘A poem often has two subjects: the starting subject and then the discovered subject. The poem wants to leave the object and go beyond it into something greater.’ You will recognize this quality in many of the works by the Monarch poets.”

Mr. Rick highlights the work of Neruda in class because he finds that Neruda’s Odas Elementales or Odes to Common Things are stunningly beautiful in their simplicity and flexible in their narrative structure. They translate readily and they speak the way seventh graders talk. “I have found the form to be highly intuitive and teachable. For our students, it’s a bonus that Neruda wrote in Spanish. I think that tends to be validating to the many native Spanish speakers in the class.”

This experience for 7th graders offers many lessons, and not just in the act of writing poetry. “This project is purposefully unrushed. I ask students to select the subject of their odes thoughtfully and to brainstorm their poems extensively before starting to write. The students rewrite, add, and delete lines from their poems to create something memorable and lasting. For many students this process changes not only how they think about writing but also about how they think about their owned lived experience,” says Mr. Rick. When students read their poems in front of an audience of friends, teachers, schoolmates, and strangers they realize that they and their stories have value.

Many of the poems tell heart wrenching stories about students’ experiences and struggles. While Ode to Video Games is certainly about video games it is more about the death of the writer’s father and her resulting struggle with depression. The poem Ode to Old Boots is about the relationship between the poet and her older brother. When their father died, the brother literally pulled on their dad’s old work boots and became provider and protector to the girl. The symbolism of the old boots and their connection between generations is quite powerful.

“I love them all, every year, because I know where each poem came from and what it took to put it on the page,” shares Mr. Rick. “I feel incredibly fortunate to be allowed to work with these students and their teacher Sally Lopez. The support from Monarch School, the Monarch School Project, and our community of friends has been formidable and encouraging from the start. I would like to offer a special thanks to the Monarch School Project and the Thomas D. Lookabaugh Foundation for paying for the printing of the books each year.”

Monarch School is incredibly grateful for Mr. Rick’s devotion to our students and to the art of poetry writing. Here are a few poems from the “More Odes to Common Things” series.

Ode to old boots

By Mariana

Brown leather

climbing boots

that were

Dad’s.

Brother

pulls them on

every morning

and

wears them

till he

lies down

at night.

Jeans, t shirt

and those boots,

creased by father

and son.

We feed the animals

together --

eight dogs and four pigs,

four puppies and

two piglets.

Brother mixes

and pours grain

into buckets.

I put the food

inside the pen

or dump it

on the grass

so the pigs

can eat that

too.

Brother looks like me

and like Dad,

who passed

last year,

died

in his sleep,

suddenly,

unexpectedly.

Brother

takes care

of me.

Makes me

feel happy,

my family,

my best friend.

When I was two

he took me

to our hometown park,

laid me

on his skateboard,

and pushed me

all around.

Now he’s 20

and we play

video games

on his Nintendo.

He’s always

cared for me,

been there

for me

when my parents

were at work

or gone,

now always in

brown leather

climbing boots,

that were

Dad’s.

From More Odes to Common Things, Volume III (2020)

Oda a viejas botas

Mariana

Botas para escalar

de cuero café

que fueran

de mi papá.

Mi hermano

se las pone

cada mañana

y

se las deja puestas

hasta que

se acuesta

en la noche.

Mezclilla, playera

y esas botas,

arrugadas por padre

e hijo.

Damos de comer a los animales

juntos –

ocho perros y cuatro cerdos,

cuatro cachorros y

dos cerditos.

Mi hermano mezcla

y vierte grano

en cubetas.

Yo pongo el alimento

dentro del chiquero

o lo tiro

en el pasto

para que los cerdos

se lo puedan comer

también.

Mi hermano se parece a mí

y a Papá,

quien falleció

el año pasado,

murió

mientras dormía,

repentinamente,

inesperadamente.

Mi hermano

cuida

de mí.

Me hace

sentir feliz,

mi familia,

mi mejor amigo.

Cuando yo tenía dos años

él me llevó

al parque de nuestra ciudad natal,

me acostó

sobre su patineta,

y me empujó

de aquí para allá.

Ahora él tiene veinte,

y jugamos

videojuegos

en su Nintendo.

Él Siempre

ha cuidado de mí,

ha estado ahí

para ayudarme

cuando mis papás

estaban trabajando

o fuera,

ahora siempre en

botas para escalar

de cuero café,

que fueran de

Papá.

Ode to Candles

By Victoria

In a room

that smells bad

they smell good.

They make me

feel relaxed.

You light them

and the wax

starts melting.

People look better

in candlelight.

Candles can

make you

really sad.

I lived with tia

and tio in

a cottage apartment

in the

Central Valley.

One summer night,

the power

went out.

We went to

McDonald’s,

hoping the lights

would be on

when we returned.

Tia found candles

in a box

in the garage

and we ate

hamburgers and

chicken nuggets in

their dim glow.

I took

a shower

by candlelight

and went to bed.

Tio blew out

the candles,

worried they

would start a fire.

I like their color,

a soft golden glow.

Once I put

my finger

in the melted wax

and let it dry

against my skin.

My great grandmother

has votive candles

in her flat

behind a big house

in Bakersfield.

There’s one with Jesus,

another with Mary

and others, I guess.

Some churches

have candles

you can light.

You leave

a coin in the box

and light a candle

and pray.

It joins

the other candles

in a group

that looks like people

in pews,

standing straight

and singing

to heaven,

neat rows

of people

with flames

for heads.

I wonder

if a tio comes

every night

to blow them out,

worried all

those prayers could

set the church

on fire.

From More Odes to Common Things, Volume V (2022)

Oda a las velas

Victoria

En un cuarto

que huele feo,

ellas huelen bien.

Me hacen sentir

relajada.

Las prendes

y la cera

comienza a derretirse.

Las personas se ven mejor

bajo la luz de una vela.

Las velas

te pueden

hacer sentir muy triste.

Viví con mi tía

y mi tío en

un pequeño departamento

en el

Central Valley

Una noche de verano,

se fue

la luz.

Fuimos a

McDonald's,

esperando que las luces

estuvieran prendidas

cuando regresáramos.

Mi tía encontró unas velas

dentro de una caja

en la cochera

entonces comimos

hamburguesas y

nuggets bajo su

brillo suave.

Me tomé

un regaderazo

bajo la luz de una vela

y luego me fuí a dormir.

Mi tío apagó

las velas,

preocupado de que

causaran un incendio.

Me gusta su color,

un brillo suave y dorado.

Una vez

metí el dedo

en la cera derretida

y dejé que se secara

sobre mi piel.

Mi bisabuela

tiene velas votivas

en su departamento

que se encuentra detrás

de una casa grande

en Bakersfield.

Tiene una con la imagen de Jesús,

otra con la de María,

y supongo que tiene otras también.

Algunas iglesias

tienen velas

que la gente puede encender.

Puedes dejar

una moneda en la caja,

encender una vela,

y rezar.

Tu vela se une

a las otras velas

y parecen personas

en las bancas de la iglesia

paradas derechitas

y cantándole

al cielo,

hileras de personas

con una llama

en vez de cabeza.

Me pregunto

si algún tío

viene por las noches

a apagar las velas,

preocupado de que

todas esas oraciones

causarán un incendio

en la iglesia.

Community Partner Spotlight: Art San Diego and Humble Design

Monarch School Project and Humble Design partnered to participate in Art San Diego’s “Access to Art” installation. Students at San Diego’s Monarch School Project sold more than 70 art pieces after partnering with Humble Design, a nonprofit interior design company in Logan Heights, at Art San Diego on September 13, 2022.

By partnering with the nonprofit, students learned many impactful lessons related to interior design, art making, exhibits and how to sell one’s art.

KUSI’s Allie Wagner went live at Monarch School to talk to students and staff about the importance of the project.